Christopher Hitchens’s toothsome memoir makes clear he has no time for postures. There is work to be done.

LIFE IS first boredom, then fear / Whether or not we use it, it goes, wrote Philip Larkin. Though he loves Larkin, essayist and critic Christopher Hitchens has always been determined to use life for all its worth, since boredom has been his life’s big fear. This has made him garrulous in the great English tradition of public arguers, but the same long tradition has also trained him to silver his volume with wit. This need for quickwittedness has also saved him in a second way, since it’s made him keep his famous drinking quite separate from his performances on paper and stage.

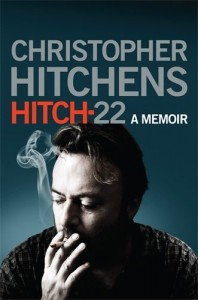

All this talk of ‘saving’, of course, leads us straight to Hitchens’ selective reputation as one of our most famous atheists. After four decades of political and literary writings, he finally wrought a bestseller with his 2007 book god is Not Great. Now, he has put out a highly anticipated memoir called Hitch-22. The peskily consonant title irritates with its missed opportunity, but Hitch-22 is a relaxed book. It sticks to chronologically themed chapters to tell the story of a career that has been public, prolific and pointy.

A lot of the ground here Hitchens has already covered in older essays, such as the dramatic stories of discovering his mother’s suicide or of discovering his Jewishness, and themes like the Rushdie fatwa and 9/11. Some stories others have already told but Hitchens wants his version on the record, such as the dinner at Saul Bellow’s his friend Martin Amis describes in his own memoir, when Hitchens ruined the evening with his ‘sinister balls’ (easy leftism). Hitch-22 does provide a few juicy revelations, mostly involving handjobs and other male encounters at school and college — reminding one of Gore Vidal’s statement that there are no homosexuals, only homosexual acts.

Vidal is a useful case in point. Hitchens has written sterling essays admiring his American elder, and the informal tutelage resulted in Vidal faxing the following encomium to Hitchens: “I have been asked whether I wish to nominate a successor, an inheritor, a dauphin or delfino. I have decided to name Christopher Hitchens.” This grand statement was swiftly withdrawn when Hitchens tore into Vidal in print over the latter’s reactionary pronouncements about 9/11.

This has been typical. Again and again, Hitchens has periodically blown up his allegiances as he revised his political position on a crucial matter. He’s steadily lost comrades on the left with his uncomfortable defences of Rushdie and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein and for attacking liberal darlings like Bill Clinton and Lady Diana. Commentators have cried themselves hoarse about his defection to the right, but they’ve never understood his International Socialist instincts — rather than which political ‘side’ he ends up on, Hitchens has been more interested in ensuring he remains a political radical rather than a reactionary.

His other instinct has been literary. While the example of close friends like Amis and Ian McEwan convinced him in youth that fiction and poetry were better left to them, he has been an outstandingly sensitive cultural and literary critic. Hitch-22 is less personal and more a cultural and political history from the 1960s onwards. In a way, the book allows you to trace the ‘line’, if you will, of modern English poetry from Auden to Larkin to, now, Fenton — alongside Hitchens’ minor obsession with pornographic ‘rude songs’. (Wrapping up our recent interview, Amis told me that he and Hitchens recently persuaded Robert Conquest to finally publish his dirty limericks — dedicated to them both. I see no sign yet of such a volume online.) Incidentally, two of the best examples of Hitchens’ ambition — of fusing the political and the literary in essay form — have occurred in the cases of Indians: his defence of Rushdie and his deconstruction of Mother Teresa.

THE MEMOIR is a lovely, golden form in the right hands. Hitchens’ familiar eloquence is again evidenced in this book’s unguarded fluency of prose. While he might be repeating his stories and opinions, the form allows him to fill in some spaces the essay won’t allow. So for example, he can finally give his minor personal impressions of Isiah Berlin — absent from his essay on Berlin — that perfectly damn the great scholar.

Hitchens has been the rare intellectual willing to go public, somone who relishes both sinking into a book review and reporting from a war-torn region. Hitch-22 relates his ease in Buenos Aires in first interviewing the dictator General Videla and then going to meet Borges. He’s been important because he’s been a man ready to work, with his motto to ‘Do something every day against Bastards HQ’. Apart from his prolific writings, he’s been a debate and speech circuit fixture, always arriving raffishly with top shirt button open and a Kurdish flag stuck in his lapel in international solidarity. It feels a bit futile to lament that he’s a dying species, especially since news last week that he’s cancelled his book tour due to a diagnosis of oesophagus cancer. On the bright side, he’s already wittily welcoming curmudgeonhood rather than hiding from it. There are lessons yet from Larkin; here’s how his poem ends: [Life] leaves what something hidden from us chose / And age, and then the only end of age.

|Published here|